i dare damnation: hamlet and laertes and religious dissonance

"to cut his throat i' th' church"

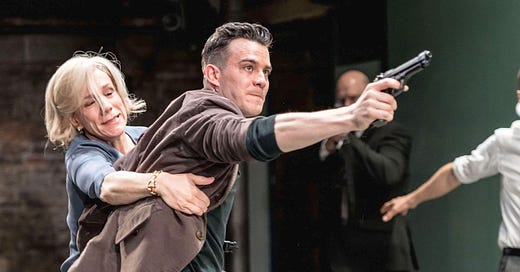

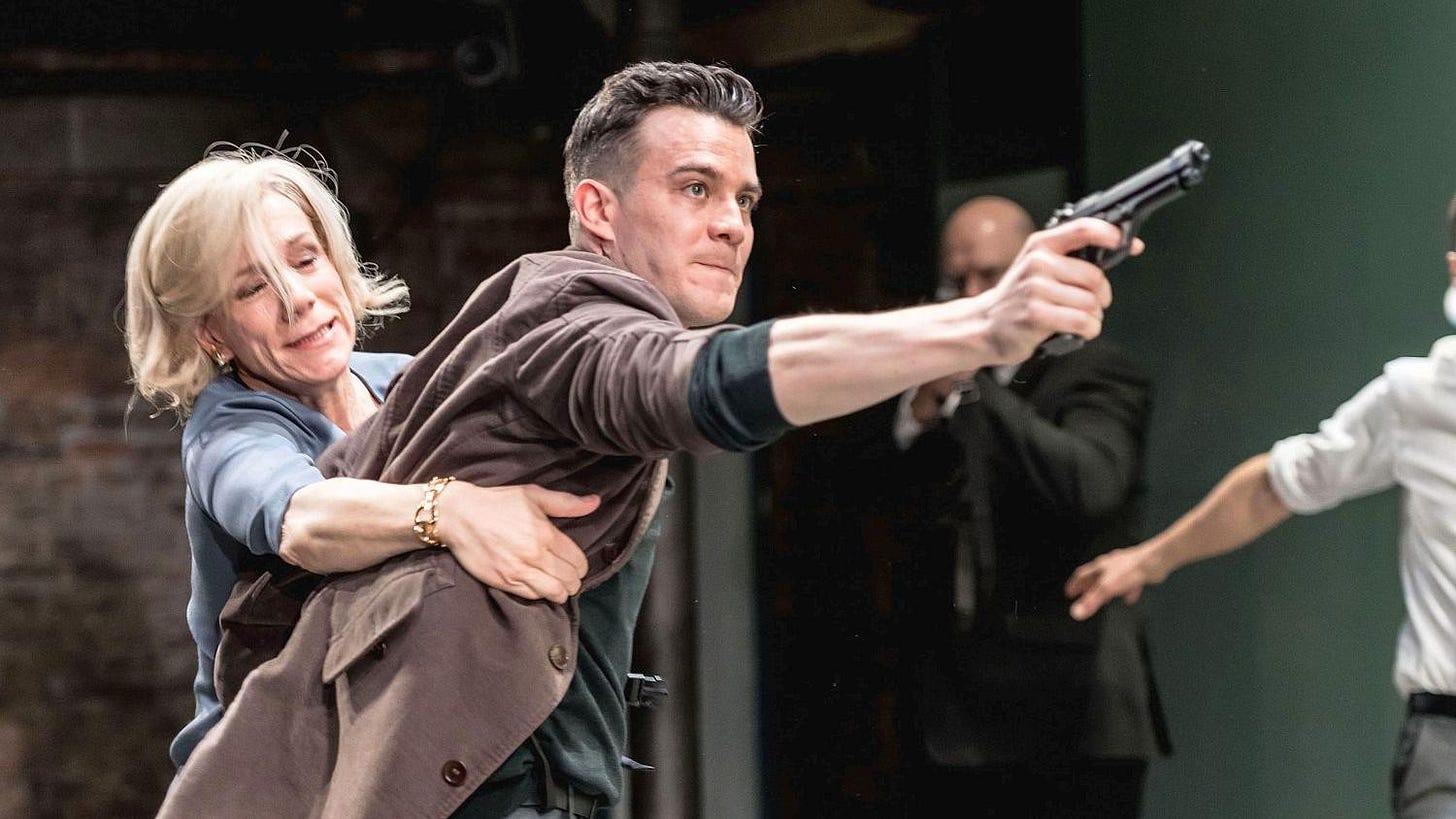

To me, Hamlet is Shakespeare’s magnum opus. None of his many brilliant works have held a candle to it. It’s tender, it’s complex, it’s witty. But I confess, I would rather watch Shakespeare than read him. So when I picked up my very dog-eared very annotated copy of Hamlet sitting black and brooding on my bookshelf again earlier this week, I also searched for a stage production to have in the background. And there it was, in all its lowercased titled glory—“andrew scott hamlet full play”. Robert Icke’s Hamlet with guns. Tailour-made for me.

As I read (and watched), I picked up on something I hadn’t in previous readings—and I owe this especially to Luke Thompson’s poignant portrayal of Laertes and Andrew Scott’s adroit understanding of Hamlet. At first glance, religion may appear to have a subtle, very “of-the-time” part to play in Hamlet. A mere embellishment to establish the attitudes of the time and place in which the play was set and written. But there is more to Hamlet than an “O God!” here and there to serve as crutch to iambic pentameter.

There is a curious and prominent discord, only harboured within two characters: Hamlet and Laertes. The two are clear literary foils, both striving to avenge their respective fathers though going about it in much different ways; Hamlet is brooding and contemplative, Laertes impulsive and emotional. Unconsidered, however, is the fact that the two can be seen as religious foils. Both share an inconsistency in their behaviours and motives, mirroring one another in much the same way as when their minds are clouded with plots of retribution.

ACT I, SCENE II

We begin with Hamlet. In his first soliloquy, we see him contemplate suicide for the first time. He desires for the very flesh of his body to melt from his bones, thawing as if ice, reduced to “a dew” he says, or perhaps “adieu”. Though we are privy to Hamlet’s bleak suicidal fantasies throughout the play, he never follows through. We see here that this is in part due to Hamlet’s deference to the “Everlasting”, as he names God, who forbids his much desired “self-slaughter”. We understand here that Hamlet does have some existing respect for God, enough for him to acquiesce to his apparent fate of condemned suffering.

ACT III, SCENE I

“To be, or not to be…” Hamlet contemplates as he contrasts self-induced death and a life of suffering. He is once again lost in the black clouds of his brain, where death looms like an evil moon and bores through all other thought. Is it nobler, Hamlet asks, to “suffer the slings and arrows” of life or to “take arms against a sea of troubles / And by opposing end them”? He compares the peace of death with placid sleep, repeating this twice over. To Hamlet, death is a door which closes off all the “heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks” the cruelty of the world has to offer upon its wretched silver plate. And so, it is something to be yearned for, longed after.

ACT III, SCENE III

Theology once again clashes with Hamlet’s ambitions when he comes upon loathsome Claudius, praying and unguarded. He sees his opportunity and intends to seize it. The imagery of Hamlet, wrathful and murderous, looming over a man on his knees in discourse with God speaks for itself. Interesting that, evil and villainous as Hamlet perceives Claudius to be, he describes his uncle-father’s death as a journey to heaven. He has every faith that God shall welcome Claudius into the Kingdom of Heaven simply because his life will be taken “in the purging of his soul”. Rather, the prince sees it best to wait until Claudius is indulging in sin, be it via drink, rage or incestuous deed; Hamlet wants him to leave this mortal plain with “heels kick[ing] at Heaven” on his way to Hell. This refusal to kill Claudius whilst he is in communion with God goes on to be juxtaposed by one single harsh line, uttered by Laertes. The question remains: if Hamlet has so much piety, so much trust in these outlined laws—why then does he himself plot and plan to kill both himself and others?

ACT III, SCENE IV

One of the more apparent scenes in which Hamlet’s faith and actions contradict one another greatly is located in Act III, whereby Hamlet enters an intense argument with his mother. In an abrupt burst of rage, Hamlet threatens her, causing her to cry out which in turn causes Polonius, spying behind an arras in Gertrude’s room, to also cry out in alarm. Hamlet stabs (or in Icke’s version, shoots) him dead from behind the cloth, unaware of his identity. Following the deed, he shows no sign of remorse, continuing to verbally spar with Gertrude: “Almost as bad, good mother, as kill a king and marry with his brother.”

The dispute continues; Hamlet makes attempt after attempt, begging his mother to see reason that her marriage to Claudius is vile. He asks her to “assume a virtue”, even if she does not really have it, repent and abstain. “And when you are desirous to be blest, / I'll blessing beg of you”, he offers, meaning once Gertrude has repented and is ready for God to bless her once more, he will pray it be so. Curious that Hamlet believes himself to be in a position of giving religious counsel—or to act as though any prayers he has to offer are worth anything—considering he killed a man not ten minutes prior. He regards his mother with a condescending tone (“I must be cruel only to be kind”), as though good and virtuous he has God’s blessing and she does not. In reality, if Hamlet follows his own unsteady rules, the both of them are dejected sinners.

Though Hamlet does promise to repent for the life he has taken, his attitudes speak otherwise. Bloodied and fallen, still and “grave” upon the floor, Hamlet jests that Polonius looks like an important man this way. This is ironic to Hamlet and he says as much, for in his life he was a “foolish prating knave”. He makes a grim pun, addressing Laertes’ father’s corpse directly: “Come, sir, to draw toward an end with you.” “Draw” meaning both to tie up a loose end and to drag. The Prince of Denmark bids his mother a simple goodnight as he drags the deceased from her chambers like a ripper.

Hamlet’s religious dissonance comes from his belief in God and the ways in which he goes against Him. He ultimately desires to die and yet cannot follow through on killing himself, for it is against his belief system. His preeminent desire to murder Claudius and avenge his father is ruled by his perception of the afterlife. Yet, he goes against his own self-imposed rules when he murders Polonius, and shows no religious guilt or true desire to repent; he is merely Hamlet, making light in every situation as always. Despite the atrocities he commits, he still believes himself to be a good follower of God and in a position to preach to others. This is a stark contrast to Laertes who, as we will see, is very much the opposite of Hamlet.

ACT IV, SCENE V

Upon hearing of the death of his father, Laertes returns from France to Denmark. He storms Claudius’ castle, demanding answers in an unstable frame of mind. He is shattered, heart pulverised and bleeding inside his chest. He will not be calm. He will not be toyed with. “To hell, allegiance! Vows, to the blackest devil! / Conscience and grace, to the profoundest pit!” Laertes cries, disregarding any morality, any allegiances that get in his way, be it patriotic, religious, ethical; “I dare damnation!”

ACT IV, SCENE VII

In Laertes’ anguished and grieving state of being, Claudius hatches a plan to take advantage of the orphaned and bereaved man. “Laertes, was your father dear to you?” He asks, almost mocking him. It is clear that Laertes loved his father—loves him still—why else would he act the way he has thus far? The foul Dane manipulates this grief, asking Laertes how far would he go to avenge his father. His answer is chilling: “To cut [Hamlet’s] throat i’ th’ church.”

Blood reaching like wicked arms across a sacred floor, marbling, coagulating; a rapier dropped upon a pew, slick as if with oil; stained glass washing a boy-heir’s drained and lifeless cheek in yellows, violets, greens.

ACT V, SCENE I

At this time, Ophelia’s tragedy has befallen her already. She has drowned herself, surrounded by the flowers which comforted her after her father’s passing. Laertes loved Ophelia dearly, and this manifests itself in a strange way. Upon her death, Laertes makes quite certain Ophelia is given a proper burial. “What ceremony else?” he asks, helplessly. He repeats his question. The priest’s harsh answer, that Ophelia is a sinner and does not deserve proper ceremony, is only another kick to the little organ behind his ribs. And unusually, Laertes insists that Ophelia will be an angel in her afterlife, violets springing from her pure corpse beneath the earth (alluding to their absence from Ophelia’s bouquet in Act IV, Scene V) while the priest will rot in Hell. Strange it is that Laertes is so concerned with and so sure of his sister’s fate in the afterlife when he has apparently crushed religion beneath his boot. That dissonance springs from the tender love he has for his sister, a hope of some kind sprouting even yet from desolate, sorrowful soil.

Heavy with misery and not yet willing to say his goodbyes, Laertes cries out “Hold off the earth awhile, / Till I have caught her once more in mine arms”, and leaps into the grave. He holds his sister and, keen for his own death to come and end his woes, begs the sexton to bury them both under a mound of dirt higher than Olympus, home of the Gods. Laertes’ own grief and pain takes priority over any religious concerns once more. He is not interested in the fact that he is desecrating a grave or interrupting a burial—a burial he fought for—he only wants to hold his sister so that she won’t be alone, even in death.

It is Laertes’ grief that acts as a catalyst to his pious dissonance; he has disowned any God, consumed by sorrow, yet still holds to Him with weak hands in some ways. He contrasts Hamlet in every way: the tortured cynic to his devout and miserable disciple. And forgiveness, such a paramount pillar of faith, is something shared contiguous with death, as though an olive branch.

ACT V, SCENE II

Hamlet, dead by Laertes’ blade and Laertes, dead by Hamlet’s blade; how telling. Laertes—forgone of any political, religious, ethical concerns—uses his dying breath to ask Hamlet’s forgiveness, and bestow his own unto him: “Exchange forgiveness with me, noble Hamlet, / Mine and my father’s death come not upon thee, / Nor thine on me!” They do not have God’s forgiveness, but they have one another’s. And both harbouring hearts bruised and buffeted by such ceaseless tragedy, by each other—doesn’t that mean so much more?